WEEK 1:

1. What the vendor side does:

(1) receive requests;

(2) break them into well-defined chunks;

(3) manage execution per chunk;

(4) reassemble;

(5) deliver;

(6) invoice;

The job is not to re-debate whether something “should be translated.” The first duty is to deliver on scope, quality, and schedule. That’s the promise the LSP makes, and that’s the ground truth we should operate on.

How I frame ownership with clients: each client sees one single point of contact “me <—> for their project”. Internally, I absolutely will coordinate with the broader PM team, but externally the experience must feel unified. This model reduces confusion, supports clear decision-making, and ensures accountability.

Team topology (how work scales): an LSP serves many clients. Each client is owned by one PM team (and yes, one PM team can cover multiple clients). Resources sit with teams, and some resources are shared.

Thoughts:

- Define resource reservation rules (who can borrow what, when), and use a visible queueing mechanism so shared linguists/engineers aren’t overbooked.

- The fastest way for a vendor-side PM to fail is to blur accountability. Single external owner + disciplined internal collaboration is the pattern that survives pressure.

2. Rate Cards: Not “Barely a Card”

What a rate card is:

A confidential summary of rates by task type: Translation, Review, DTP, LSO, etc. (negotiated and agreed by both sides) (freelancer included).

Clients should never see other clients’ quotes.

leaking invites “are we over/under-charged?” distrust and damages the relationship.

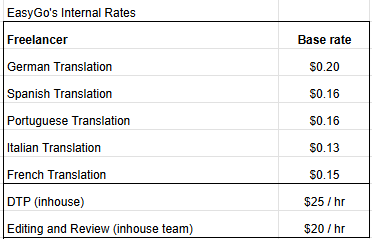

Leveraged (Trados-style) rates: industry-standard because we leverage CAT/TM.

Three components:

- Base rate = fully new content

- Fuzzy rate = partial TM match

- Match rate (100%) = complete match

Different CAT tools label the bands differently, but the economics are the same.

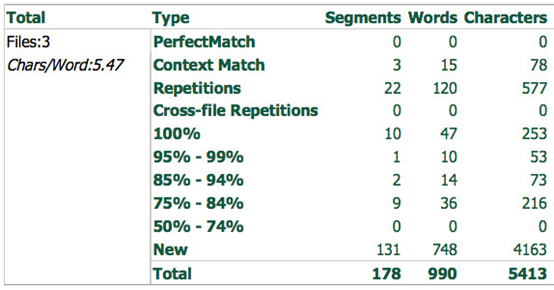

Activity 1.1: Spreadsheet First, Calculator Never

In future projects, rate cards will inevitably involve elements such as base/fuzzy/match ladders, per-language differentials, and task add-ons (terminology work, engineering, desktop publishing).

When managing these, the ultimate goal will be to build automation into the quoting process so the system can scale across 20–30 locales, rather than relying on manual calculations.

Takeaways: use formulas, replicate with copy/paste, and use checksums to catch errors.

My thoughts & extension: at scale, quotes are systems problems, not arithmetic problems. When I managed vendor quoting on the buyer side, I built a set of Google/Feishu Sheets that included the following elements. (Partially, just for future reuse):

- Named ranges + VLOOKUP/XLOOKUP for rate pulls

- SUMPRODUCT for fuzzy-band rollups

- Data validation for locale/task selectors

- Cross-sheet checksums (e.g., word-count totals must reconcile to source analysis)

- Cross-sheet references (Link data across different sheets (e.g., pulling figures from a “detail sheet” into a “summary sheet”) to keep info synchronized and reduce duplicate input.

- Protected cells to freeze business logic

What’s Important: SAVE TIME & ELIMINATE MANUAL ERRORS.

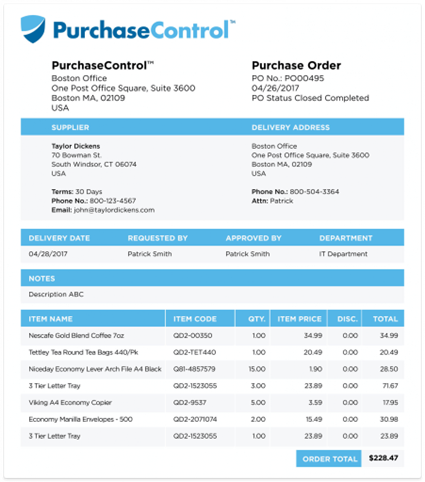

3. POs:

What a PO does:

- Signals formal intent to buy

- With Finance, locks funds so vendors can invoice against real money

- Creates the first half of the purchase

What a PO must include: (1) what is being bought, (2) for how much, (3) delivery deadline; nice-to-haves include condition, delivery to whom/where, and a PO reference. Issue concrete POs downstream so freelancers feel safe starting work.

PO vs Invoice: - PO = buyer’s commitment to purchase on specific terms (pre-delivery).

- Invoice = seller’s request for payment for delivered work (post-delivery, referencing the PO).

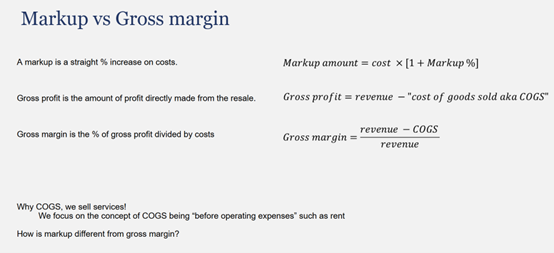

4. Markup vs. Gross Margin

Definitions:

- Markup = % added on cost when setting the price.

- Gross profit = Revenue − COGS.

- Gross margin = Gross profit / Revenue.

Markup vs. Gross Margin

Thoughts:

- Markup is cost-based. It shows how much percentage is added on top of the cost to determine the selling price.

- Gross Margin is revenue-based. It shows what percentage of the selling price remains as profit after costs.

In practice, markup reflects a pricing perspective: how to set the price over cost, whereas gross margin reflects a profitability perspective, showing how much of the revenue translates into profit.

So…What Value Does an LSP/PM Bring When “Reselling” Translation?

Thoughts:

(1) Quality governance: define the bar, instrument it (style guides, termbases, translation memory), and enforce it through review loops (not just “find a translator.”)

(2) Risk management: coverage for vacations, bench strength, backup linguists, and shift handoffs across time zones.

(3) Engineering: preflight, regex extraction, placeholder protection, segmentation rules, TM cleanup, and DTP handshakes that prevent expensive rework.

(4) Vendor: finding the right freelancers (experience with the content and genre, domain fit, locale nuance), maintaining scorecards, and mentoring to improve over time.

When these are present, markup is earned. When they’re absent, markup is a tax. :)

WEEK 2

1.The PO - Invoice Loop

A Purchase Order (PO) expresses the buyer’s desire to purchase, while an Invoice is the seller’s request for payment after delivery.

So this becomes a loop: The client issues a PO to the LSP, the LSP delivers work, and then invoices back. Similarly, the LSP issues POs to freelancers, who later invoice for their completed tasks.

Takeaway: As an LPM, you’re simultaneously a seller to your client and a buyer to your vendors. The real value is in managing and tracking both sides consistently. If either side falls apart, for instance, late POs, mismatched invoices, missing references, cash flow and trust collapse.

2. Types of POs in Localization

Minimum information

- The document name “Purchase Order”

- The Buyer Company and its business details

- The Seller (company?) and its details

- The PO number and date of issuance

- What is being purchased, at what rate, quantity, and total prices.

Some may also include other details such as:

- Required delivery date

- Payment terms

- Any special notes

Go deeper into Blanket POs (BPOs), which cover multiple tasks or periods under a single umbrella (e.g., “all translation work in Q2 up to $20,000”). This is common in LSP–freelancer relationships because it avoids the overhead of issuing one PO per micro-task.

The BPO is still a PO. It must contain the same essentials: total amount, validity period, and at least a general description of services.

3. When Do Pos End?

- Expiration = calendar-based stop.

- Termination = discretionary stop. (contract disputes, budget freezes, or a change in project scope…)

- Replacement = continuation under a new number.

- Exhaustion = budget/fund-based stop.

4. Activity: What are the variables on the invoice?

Likely change from invoice to invoice:

- Itemized list of goods and services

- Taxes, fees, and discounts

- Invoice date

- Total due

- Subtotal

- Invoice number

May change but less frequently:

- Customer PO number (especially if BPO)

- Special notes

Notes: Special notes usually stay the same (e.g., “Thanks for your business”), but sometimes you need to add case-specific instructions like “Happy Holiday!”, “Wire transfer only” or “Late delivery penalty waived.”

Will almost never change:

- Title "Invoice"

- Your customer's business information

- Your business information

- Payment terms and banking information

Notes: Your payment terms (e.g., Net 30) and your company’s bank account details are contractual and standardized. Unless you formally renegotiate terms or change banks, these fields are static across all invoices.

5. The Approval Role

As PM, our job isn’t to pay invoices or handle payment from the client. Our role is to approve: check that the invoice references the right PO, matches the delivered work, and is within expected ranges.

Cash handling is done by:

- Account Payable (AP): This team pays your providers based on their invoices

- Account Receivable (AR): This team collect payments from your clients based on your invoices

The principle: PO says what should happen, while invoice says what did happen. LPM verifies the match.

6. AP, AR, and the Separation of Duties

Why can’t PMs just handle money directly? Project management and cash handling require different skill sets and should therefore be evaluated as distinct functions.

Make units. That’s why enterprises divide functions.

- AP (Accounts Payable) pays vendors.

- AR (Accounts Receivable) collects from clients.

- PMs (Program/Project Managers) create and validate the business logic (what’s being bought/sold).

This separation enforces controls, prevents fraud, and ensures reporting consistency under US GAAP.

Thoughts:

It also explains why LPMs often feel like “middlemen.” But that’s not a weakness, it’s the design. Our credibility comes from keeping the logic and paperwork tight, so Finance can confidently move the actual money.

WEEK 3:

1. Cash vs. Accrual Accounting (Video: linkedin.com/learning/a-guide-to-understanding-financial-statements/cash-vs-accrual)

One of the key concepts this week was the difference between cash-based and accrual-based accounting. Under a cash basis, revenue and expenses are recorded only when cash actually received or paid, not when they are incurred. This approach is simple and works for small businesses or individuals, but it has the drawback of not always giving readers of financial statements a full picture of business health.

By contrast, accrual accounting records revenue when it is earned and expenses when they are incurred, regardless of when cash is received or paid. This provides a clearer view of profitability by aligning revenues and expenses to the correct period. However, it comes with challenges, such as reconciliations are more complex and time-consuming, requiring stronger systems and oversight.

2. In-Class Discussion:

In practice, accrual requires us to distinguish between two key moments: when something is completed and invoiced, and when work is still in progress but not yet invoiced. The invoice itself is critical. It is the final document of the transaction and serves as evidence of revenue recognition. Fundamentally, accrual is about matching work completed to financial reporting, so managers will have a more accurate picture of what has been accomplished.

Also, financial results are always reported over a period of time. For example:

- A coffee stand might operate on a cash basis, tracking revenue daily.

- A small one-person localization agency might also use cash basis, tracking monthly.

- A large enterprise, particularly if publicly listed, will use accrual basis, tracking monthly or quarterly.

3. Activities and Notes:

- Activity 1: If invoices are issued and paid immediately, gross margin is unaffected by whether cash or accrual is used.

- Activity 2: Under cash basis, if only invoices are tracked, growth trends appear steeper because costs are recognized later. This may give a false sense of rising profitability.

- Activity 3: Net terms on invoices (“Net 30,” “Net 60,” etc.) matter. They define how long a client has to pay, and are often negotiated. In B2B transactions, immediate payment terms are rare.

In accrual, businesses are expected to evaluate or estimate work completed, even if not invoiced yet. In cash-based small businesses, revenue and costs are often separated in time, which can inflate perceived profits and give a misleading impression of business growth.

4. Am I productive? Am I worth my salary to my employer?

- Managing larger volumes of revenue;

- Working on more profitable product lines;

- Improving margins through efficiency or technology;

- Optimizing vendor costs (e.g., hiring freelancers);

- Growing business with clients.

5. Thoughts & Insights:

In my opinion, while financial KPIs provide clarity and make comparisons easier, they don’t capture the full value a manager brings. From my own work experience, performance evaluations also look beyond the specific revenue a manager delivers in a single quarter. A more balanced approach would be to combine financial outcomes (e.g., managing more revenue, improving profitability, reducing costs) with non-financial KPIs (e.g., client satisfaction, team collaboration, innovation). Looking at both gives a clearer picture of how an employee creates value, both strategically and operationally.

WEEK 4:

1. What is the value to the client?

- Project management: breaking down large, ambiguous requests into executable chunks and ensuring they are delivered on time and at the right quality.

- Access best practice access: offering clients the benefit of practices without requiring them to build the expertise in-house.

- Reduce risk

- Outcome consistency: ensuring deliverables are standardized and predictable across projects and time.

- Additional capabilities: enabling access to services like large-scale translation, DTP, or technical toolchains (TMS, QA frameworks) that clients neither need nor want to maintain internally.

2. In-house departments

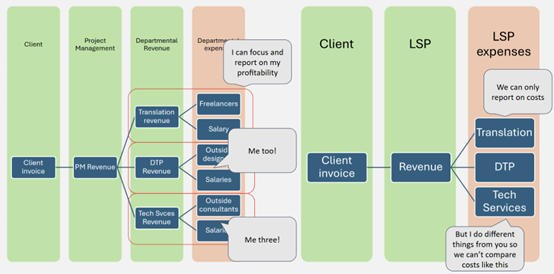

Large LSPs often operate with multiple in-house departments (e.g., TEP, DTP, Engineering). These departments may rely on internal employees or external freelancers/contractors, but either way, they function as revenue centers. They do not provide their services “for free.”

For the PM, this creates an internal economy: although the PMO invoices and collects payment from the client, it must distribute revenue to other departments, often through internal POs. Each department thus maintains accountability for its contribution and profit.

3. Additional capabilities = Departmental revenue

Each department actively generates revenue by charging a markup on its resources:

- A TEP department may charge the PM a higher per-word rate than what is paid to freelancers.

- A DTP department may hire designers at $X/hour but invoice the PMO at $Y/hour.

- Solution Architects draw a salary from the same company as you but will charge you (as the PM) a consulting rate.

This means departmental revenue is not abstract—it is a formal mechanism for ensuring that every group “earns” its share of client revenue. The PMO essentially acts as a hub, redistributing funds through internal transactions.

Thoughts (also through this week’s assignments): I see this model as both an efficiency driver and a potential friction point. On one hand, it encourages each department to act as a business unit. On the other hand, it can create tension if every department increases its markup, forcing PMs into a balancing act, protecting margins without pricing the LSP out of the client relationship.

4. Value of separate departments

From the PM’s perspective, the existence of specialized departments reduces workload and brings critical expertise into projects. For the company as a whole, departmentalization improves revenue retention by ensuring profit margins are captured at multiple stages rather than diluted.

5.Why use departmental revenue?

With departmental revenue, each function (Translation, DTP, Tech Services) records both revenue and costs, so it can report on its own profitability. This creates accountability and ownership across departments.

Without it, the LSP only sees aggregate revenue and expenses. Because each function does different work, costs cannot be compared meaningfully, and profitability by department becomes invisible.

Thoughts: Departmental revenue turns each group into a business unit. It clarifies performance, supports fair internal negotiations, and makes external blended rates easier to explain.

WEEK 5:

1. Pilot Projects and Estimates: Who gets involved?

When projects move from planning into execution, different stakeholders become involved depending on the stage and scope:

- Program and Account Management: oversee the client relationship and project alignment.

- Sales and Account Management: handle the commercial side, including contract negotiations.

- Legal: review and approve sales contracts.

- Service teams: Language Services, Multimedia, and Technical Services execute the work.

- Solution Architecture: where applicable, ensure services and technologies connect seamlessly into a coherent solution for the client (e.g., AI-enabled localization, broader solution design rather than narrowly scoped technical tasks).

2. Pilot projects

A pilot project is essentially a small-scale, real-world test before committing to full implementation. Its purpose is to validate feasibility, effectiveness, and cost under controlled conditions.

Key characteristics:

- Conducted with real data and real circumstances, but on a smaller scale.

- Subject to more intense monitoring and troubleshooting than standard delivery.

- May lead to modifications, or cancellation, if outcomes reveal critical flaws.

Supporting pilot success requires deliberate actions:

- Bring the A-team to ensure quality execution.

- Understand client assumptions and goals to align delivery with expectations.

- Maintain clear, consistent communication throughout the process.

Pitfalls to avoid:

- Do not offer unsustainable discounts in hopes of future work.

- Do not lose sight of the underlying concept being tested.

- Do not cover up issues—pilots are designed to surface problems, not hide them.

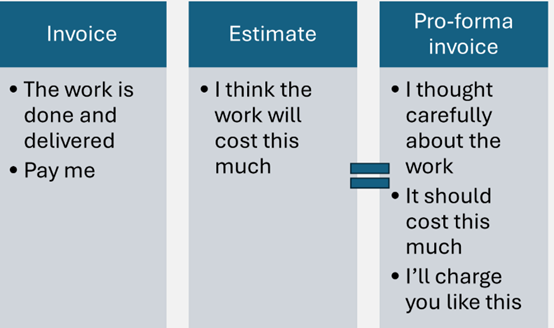

3. Estimates and pro-forma invoices

Clients often need formal documentation of expected costs before they can request new budget. This documentation may take the form of:

- Estimates

- Quotes

- Pro-forma invoices

Unlike invoices, these are not demands for payment but rather cost projections that allow the client’s finance team to evaluate feasibility and allocate funds.

Thoughts: From a PM perspective, this highlights how financial documentation is not just administrative overhead—it’s a strategic driver. Without it, the project never secures internal funding. Providing accurate, professional estimates signals credibility and smooths the path for future work.

WEEK 6:

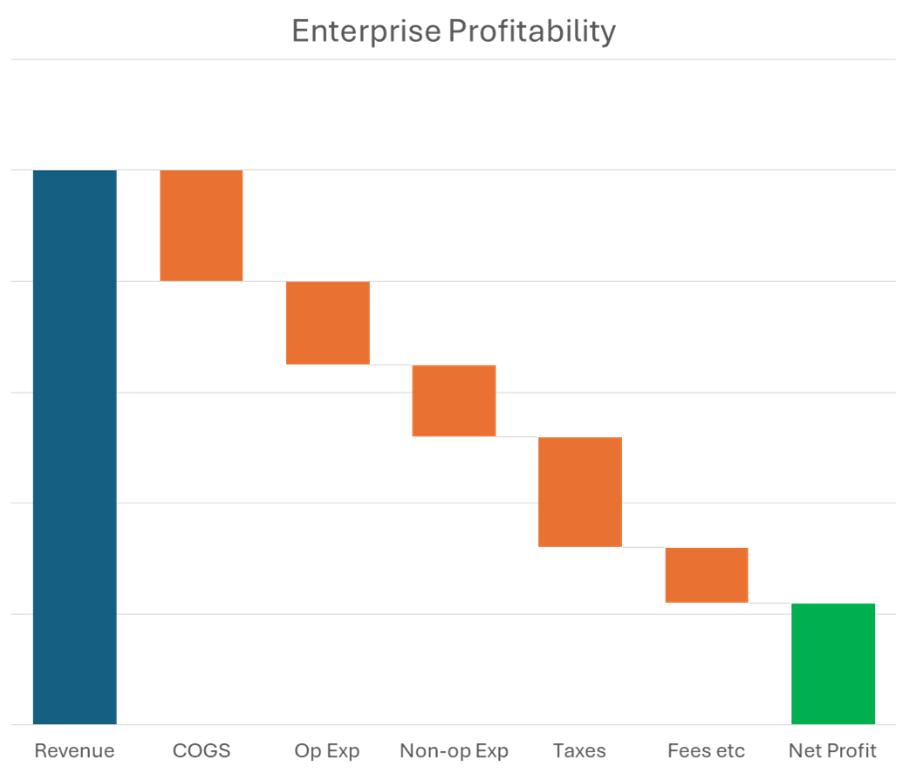

1. Understanding Enterprise Profitability

This week focused on the three layers of enterprise profitability: gross, operational, and net, and how they interconnect.

- Gross profit = Revenue − Direct costs of producing goods or services. This reflects how efficiently the company produces its core deliverables. → For L10N Project Managers, this is typically the main focus area: managing vendor costs, workflows, and efficiency to maximize gross margin.

- Operating profit = Gross profit − Operating expenses (SG&A: sales, general, and administrative).

This level measures how efficiently the company runs itself. Typical expenses include salaries, rent, utilities, and marketing. - Net profit = Operating profit − Interest, taxes, and other non-operating costs.

This reflects the company’s final financial health after all obligations.

Op Margin = OP Profit / Revenue (x100%)

Thoughts: As localization PMs, we operate almost entirely within the “gross” layer. Our decisions: vendor selection, workflow optimization and automation will directly shape gross margin, even though we don’t usually see the operational or net layers. This reinforces the idea that PMs influence profitability not by cutting costs arbitrarily, but by increasing efficiency and predictability in project delivery.

2. Fiscal Year and Year-End Closing

Most companies define a fiscal year differently from the calendar year. As the fiscal year closes, each department must complete financial reporting tasks to ensure all revenue and costs are correctly recorded. For LPMs, this involves:

- Invoicing all billable work.

- Minimizing accruals by ensuring work is invoiced whenever possible.

- Documenting all expenses and validating received invoices.

- Closing open POs to end payment obligations.

Collaboration is required at multiple levels:

- Client-side: confirm any uninvoiced work and clarify reasons.

- Vendor-side: ensure all provider invoices are received before the cutoff.

- Internal teams: confirm departmental revenue and complete internal accounting tasks on time.

Thoughts: The process highlights how critical timing and communication are in financial management. Year-end closing is not about last-minute rushes, it’s about ongoing discipline. Regular monthly reconciliations make EoY tasks manageable, while poor tracking accumulates into chaos.

3. Activity (The Correct Chronological Flow)

The logical sequence of tasks before fiscal year close should be:

- Invoice clients for all remaining billable work.

- Complete internal departmental revenue tasks (issue or confirm internal POs/invoices).

- Review and approve all provider invoices.

- Close open provider POs.

- Calculate and report accruals if required.

Equally important is communication:

- Notify clients that invoices may be sent earlier than usual due to fiscal year deadlines.

- Remind vendors to submit invoices before the cutoff date.

- Inform internal teams of their accounting deadlines for departmental revenue confirmation.

- Once everything is reconciled, confirm with vendors that all open POs are closed and provide visibility on when new POs will be issued.

4. Tips for a Smooth Year-End Close

To ensure the process runs efficiently:

- Communicate early with all stakeholders.

- Clarify expectations, especially with new clients or providers.

- Follow up periodically and send reminders.

- Minimize nonessential communication during the crunch period.

- Use existing templates for manual reports.

- Maintain monthly progress tracking to prevent year-end backlog.

Thoughts: I think this week reinforced the idea that financial closure is not an accounting task, but a project management one. The same principles apply: define scope, align timelines, communicate proactively, and verify deliverables. EoY is essentially the “delivery phase” of financial operations, where precision and coordination determine the credibility of the entire organization.

WEEK 7:

This week is a key transition from the vendor perspective to the client side.

As localization managers inside an enterprise, we move from being a profit center to a cost center. Our performance is no longer measured by direct profit, but by how effectively we help other teams achieve company goals with limited resources.

1. Organizational Context and Role Shift

As the newly hired Localization Manager under the Global Operational Support team, the immediate task is to align with this long-term direction while executing short-term deliverables efficiently.

The primary difference from vendor-side work lies in accountability: we no longer sell services externally but enable internal stakeholders to deliver consistent, localized experiences. This requires budget discipline, stakeholder communication, and process transparency rather than revenue generation.

2. BHAG and SMART Goals

A BHAG sets a long-term vision: Big, Hairy, Audacious Goal. SMART goals, by contrast, are

- Specific - the goal specifically addresses an aspect of the business;

- Measurable - the goal is set to measurable metrics;

- Attainable - the goal can realistically be met

- Relevant - these goals can contribute to our success

- Time-based - must be achieved within a time frame

3. Budget as a Planning and Control Tool

A budget is a structured plan that forecasts future spending and compares it to actuals. It enables managers to justify expenses, monitor deviations, and adjust allocations as needed.

The essential components include:

- Planned or budgeted or forecasted expenses (and revenue),

- Actual or current expenses (and revenue)

- Line items on where money is being spent (or made)

- Rationale on why actual did not match planned, and what will be done about that

This plan–actual–variance loop forms the backbone of cost management. Effective budgeting requires anticipating potential fluctuations and keeping a margin of safety (in case, 10%). Importantly, this buffer is not an allowance for overspending but a safeguard for unexpected costs.

4. Purchase Orders & Cost Allocation

The PO total should include the estimated cost plus the safety margin, ensuring financial flexibility without exceeding approved limits. Budgets are often distributed across months according to project phases—file preparation, translation, DTP, and QA—each carrying proportional costs. The logic should remain consistent and justifiable when presented to finance.

5. Cross-Department Alignment

Client-side localization success depends on collaboration. Marketing drives awareness, sales drive revenue, and localization ensures both are accessible to new markets. Clear communication about scope, deliverables, and budget ownership prevents misalignment.

Prioritizing languages (e.g., FIGS + Nordics) should follow the company’s market expansion strategy, aligning language investment with measurable impact.